-

Sprituality In Architecture

October 2011

“……………..spirituality includes the conviction that there is more to the world than what the eye sees, that man can relate to the unseen aspects of it, and in so doing their own being is enhanced.”

By Nandaka Jayasinghe

Throughout history many cultures have devoted vast resources towards their sacred architecture resulting in some of the most impressive structures created by man. It is thus evident, how spirituality has played a major role in shaping the built environment. From ancient Mesopotamian ziggurats to European cathedrals, cities have literally served as centers of sacred practices and religion. So much so that even the History of Architecture follows the history of religious built forms.

Man has always been drawn towards spirituality. His need to relate to “the nature of things” has often been fulfilled by that which is considered as sacred. Spirituality on the other hand, deals with a highly subjective perception, which may or may not directly be related to what is considered sacred.

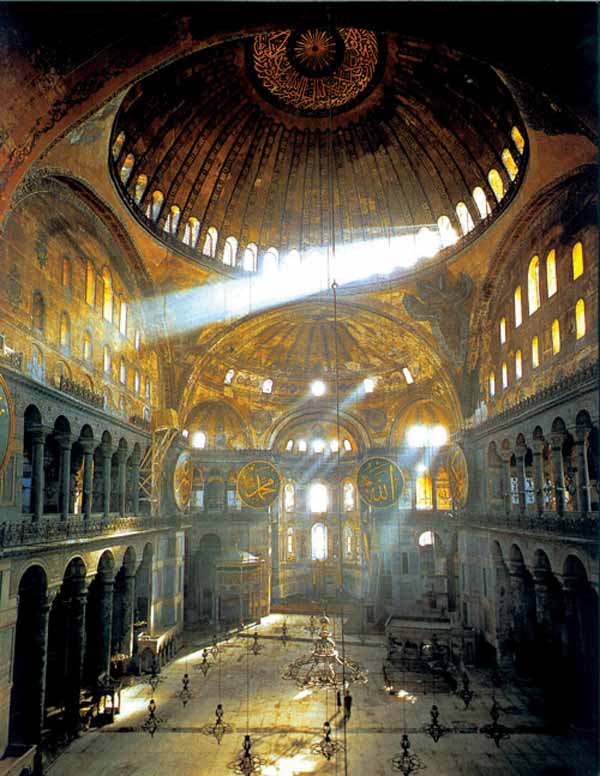

Geometry, iconography, the use of signs, symbols and religious motif are part and parcel of the architecture of sacred buildings. While these may serve as building blocks used to identify a specific building typology; they play no major part in making the building or its internal spaces spiritual. In order to achieve spirituality the physical aspects of a space such as its volume, degree of enclosure, the play of light, use of materials etc. must be carefully manipulated.

Spirituality could be described as a heightened state of mind in which one perceives the action of forces beyond self-limited consciousness. This spatial character is evident in the architecture of medieval cathedrals, which comprise spaces with intimidating volume and very few direct views of the outside world, suggesting to its users to look inwards and contemplate. These spaces would either be flooded with light pouring in through stained glass windows or lit up with streaks of light falling in through openings placed at a height, adding comfort and a sense of mysticism to the space.

These characteristics can be seen in the Hagia Sophia of Istanbul, a building which is revered as a spiritual space by people the world over. This massive domed structure was originally built by the Romans in the 6th century AD as a Christian basilica, it was converted to a mosque by the Ottomans in the 15th century AD, and is presently a museum which pays due respect to both religions. This goes to shows how the spiritual quality of a space transcends the religion of its users.

Over time the architecture of religious buildings have evolved, though architects may have stepped away from the generic attributes of these buildings, the spiritual characteristics of spaces have been retained and enhanced in different methods. Towards the latter stages of his career Swiss architect Le Corbusier designed two very unique chapels, Ron Champ and the church of Firminy in France. They look nothing like what a conventional church or chapel would look like, however these completely introverted organic shaped structures achieve a spiritual spatial quality through the playful creation of volumes and wall fenestrations which bring in light. The starkness of the concrete wall finishes adds a serene quality to the space which is punctuated by the sharp coloured paint accents which break the monotony and add interest.

Sprituality in architecture isn’t achieved solely through contained inward looking spaces. The monolithic concrete structures designed by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando are good examples which illustrate this. The church on water has an outward looking chapel space which as the name suggests looks out on to the breath taking scenery across a large pond of water. The scenery provides the backing for a cross placed on the water. It is a space for outward contemplation, looking out beyond one’s self. In contrast his design for the church of light in corporate a small chapel space which culminates in a cross shaped opening on the wall creating a very strong focal point.

Spirituality is not just confined to the experience of static spaces it is also associated with the experience of moving through a space or a series of spaces. This characteristic is evident in the forest monastery complexes of Mihintale, Arankale and Ritigala. The landscaped pathways between buildings are in harmony with the natural environment at times forging through conforming to axial geometry and at time undulating in organic paths paying respect to the existing natural environment.

At times it is the intention of the architect to create spiritual spaces in buildings which are secular in nature. The work of Peter Zumthor is almost always of this nature. Be it a spa in the alps or a museum in a tight urban context, his use of material and the manipulation of light result in pleasant serene spaces, capable of allowing it’s user’s to have experiences which are spiritual in nature.

“Gravity builds space, light builds time, and gives reason to time. These are the central equestions of architecture: control of gravity and dialogue with light.”

Alberto Campo Baeza